Soil Chemical Properties

Chemical properties of soils encompass several key aspects, including the inorganic matter in soil, the organic matter in soil, the colloidal properties of soil particles, and the reactions and buffering actions in acidic and basic soils. The chemical side of a soil is vital, of course, and is about the correct balance of the available nutrients in the soil. This is primarily determined by the organic-matter content and its humus percentage; this is the ‘storehouse’ of nutrients on any farm. The extent to which minerals have a dominant presence or not affects the release of specific nutrients. Supplementing shortages is essential, but the right balance is even more important. The soil only produces nutrients if you have the right balance. Chemical and physical properties impact biological properties. Optimal chemical and physical properties will lead to optimal biological properties and soil functions i.e. nutrient and water cycling.

Contaminants

A soil contaminant is any substance that exceeds naturally occurring levels and poses a risk to human health. The most risks arise in urban and former industrial areas. Common contaminants include heavy metals such as lead, pesticides, petroleum, and other substances resulting from past human activities.

Micronutrients

Micronutrients (sometimes also called trace elements) are essential plant nutrients required in tiny amounts to sustain plant growth and development, especially enzyme systems related to photosynthesis and respiration. The main essential elements in this group usually include boron, chlorine, copper, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, and zinc.

Carbon to Nitrogen Ratio (C:N)

The carbon-to-nitrogen ratio in soil is the ratio of the mass of carbon-to-nitrogen. A C:N ratio of 10:1 means there are ten units of carbon (C) for each unit of nitrogen (N) in the soil. This ratio can have a significant impact on how the soil functions; i.e. crop residue decomposition, particularly residue-cover on the soil and crop nutrient cycling (predominantly N).

It is important to understand the C:N ratio when planning cash crop rotations and cover crop rotations. Soils with a carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio of 24:1 have the optimal ratio for stimulating the release of nutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and zinc, to crops. This ratio influences the amount of soil-protecting residue cover that remains on the soil. It is important to understand these ratios when planning cash crop rotations and cover crop rotations. For crops and cover crops with a low C:N ratio (hairy vetch, 11:1), the quicker microbes consume residue, the less time soil is covered.

Salinity

Soil salinity is caused by excessive levels of water-soluble salts in the soil water. Soluble salts are a combination of positively and negatively charged ions, such as table salt (Na+Cl–). Water-soluble salts directly affect seed germination and plant growth as high levels of ions (positive and negative) from soluble salts restrict normal water imbibition (absorption) of the seed and uptake by plant roots, even when soils are visibly wet, resulting in delayed and poor seed germination and drought-stressed plants (osmotic effect). Often, clear visual symptoms of salinity can be observed at the soil surface in the form of a salt crust. Once the water content becomes less than the solubility of the salts, the ions recrystallize, forming visible “salts” on the soil surface or within the soil profile.

In addition to competing with plants for water, certain salts, such as Na+Cl–, can also cause ion imbalance and toxicity in plant cells. Soil salinity levels are measured in the field or by sampling the affected areas and submitting them for analysis by a soil laboratory for Electrical Conductivity (EC). It is important to note that salts do not cause deterioration of soil structure. In fact, if calcium (Ca2+)-based salts are dominant, Ca2+ ions encourage the aggregation of soil particles, a process known as flocculation (clumping together), resulting in well-defined pores that facilitate the free movement of water through the soil profile.

Secondary Nutrients

Secondary nutrients are nutrients that slightly limit crop growth and are moderately required by plants. These nutrients are calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and sulfur (S). Secondary nutrients are as significant as primary nutrients in plants, but they are needed in smaller quantities.

Organic Matter

Organic matter is the organic fraction of soil, consisting of plant, animal, and microbial residues at various stages of decomposition, the biomass of soil microorganisms, and substances produced by plant roots and other soil organisms (e.g., sugars, amino acids, organic acids, etc). Organic matter offers a range of biological, chemical, and physical benefits to soil, serving as the foundation of the soil food web. Soil organic matter is an essential indicator of soil health.

Soil organic matter and soil organic carbon are similar terms and are often used interchangeably. However, they are not identical. Organic matter refers to the entire pool of organic material in the soil, including carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur, and other elements. Organic carbon refers to only the carbon component of soil organic matter. Researchers estimate that carbon accounts for about 58% of the soil organic matter.

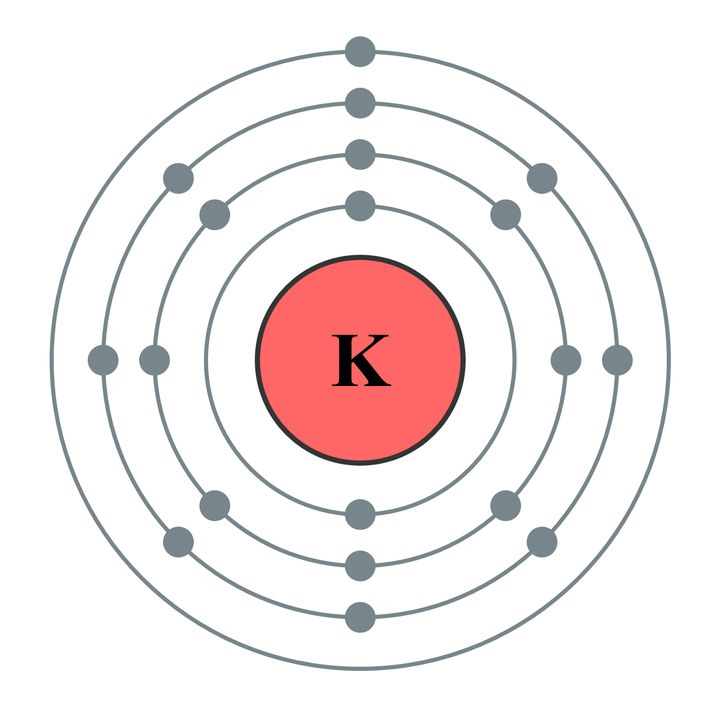

Potassium

Potassium is an essential plant nutrient used in key intracellular processes for supporting plant growth, including sugar and nutrient transport, stomatal regulation, photosynthesis, and acting as a catalyst for plant enzymatic processes. Availability to plants is heavily controlled by the form in which potassium is found in the soil, which may include forms such as exchangeable potassium, soil solution potassium, fixed potassium, and unavailable potassium.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus is a nutrient essential for plants in several complex functions, including energy transformation, photosynthesis, nutrient movement, sugar and starch synthesis, and genetic transfer. The general forms of phosphorus in the soil include plant-available inorganic phosphorus as well as plant-unavailable forms such as organic phosphorus, adsorbed phosphorus, and primary mineral phosphorus.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is an essential plant nutrient required for growth, development, and reproduction, and it is a crucial component of organic molecules, including proteins, amino acids, and nucleic acids. Additionally, it plays a crucial role in various key plant metabolic processes, including photosynthesis.

In soil, nitrogen may be found in two forms – mineralizable and plant available. Mineralizable nitrogen is found in organic soil components, and for plant use must be mineralized, or broken down, to simpler forms. Plant available (mineralized) nitrogen is in a form that can be readily utilized by plants and is commonly found in nitrogen forms such as nitrate (NO3) and ammonium (NH4).

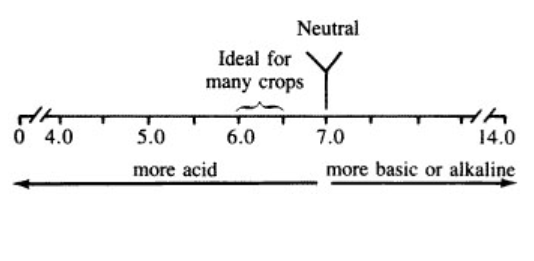

Soil pH

Soil pH is an indicator of how acidic, neutral, or alkaline (basic) a soil is, based on the hydrogen ion concentration. The pH scale is reported as a negative logarithm and ranges from 0 to 14. Common classes of soil pH include: extremely acidic (3.5-4.4), slightly to extremely acidic (4.5-6.5), neutral (6.6-7.3), and slightly to extremely alkaline (7.4-9.0). A pH range of 6.0 to 7.0 favors the growth of most crops, although some crops have specific acid or alkaline soil requirements to be productive. Understanding soil pH helps to comprehend the influences of soil chemistry and biology, as well as how nutrient availability and soil organic carbon are affected. To guide you in the selection of an article, the Soil Nexus team suggests that you choose an article based on soil types of interest, which are often typical of a geographical region.

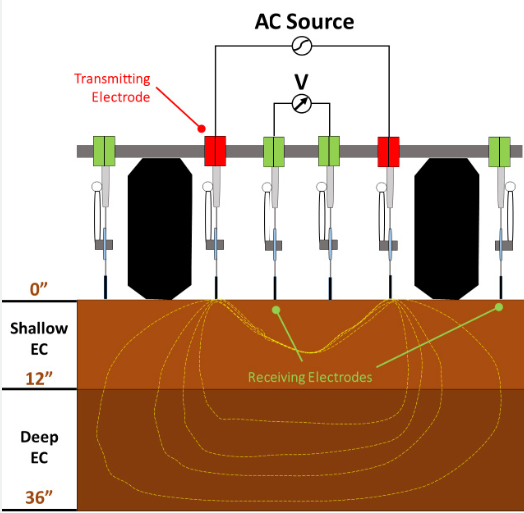

Electrical Conductivity

Soil electrical conductivity (EC) is a measure of the concentration of ions from water-soluble salts in soils, and the test results are indicative of soil salinity. EC is the ability of a material to conduct an electrical current, and it is commonly expressed as dS/m or millimhos/centimeter (mmhos/cm). One dS/m = 1 mmhos/cm. Soil EC is inversely proportional to the electrical resistance in the soil solution. EC is measured by passing an electrical current through the soil solution. Water-soluble salts in the solution enhance the transfer of electric current (electric conductance).

There are two common methods to analyze soil EC: 1:1 soil:to:water ratio and the Saturated Paste Extract Method. In the 1:1 soil:to:water ratio method, an equal amount of deionized water is added to a similar amount of soil (for example, 400 grams of soil with 400 ml of deionized water). After thoroughly shaking and mixing the soil with deionized water, the EC meter is used to measure the EC value. This method, however, yields EC results that are two to three times lower than those obtained through the Saturated Paste Extract Method, depending on the soil texture. In the Saturated Paste Extract Method, deionized water is slowly added to the soil sample until it forms a glistened, thick saturated paste. Depending on the texture, soil samples may require less or more water to become glistened, thick, and saturated pastes. Then water is extracted from the paste under vacuum pressure. Finally, the EC meter is used to get the EC number of the water extract. This method eliminates the soil texture factor and is considered the most accurate method for analyzing soil EC.

For classification purposes, a soil is considered saline if the saturated paste extract electrical conductivity (EC) equals or exceeds 4 deciSiemens per meter (dS/m). However, in terms of crop production, even an EC of less than 4 dS/m can result in considerable yield loss, for example, in the case of soybeans. Additionally, soil electrical conductivity is an indirect measurement that correlates closely with several soil physical and chemical properties.

Note: An ohm is a unit of resistance, and an mho is a unit of conductance. “Siemens” was adopted as a scientific representation of mho in an 1881 conference in England to honor a prominent scientist of the period who studied electrical conductance. Mho is usually used by lay soil scientists today, although dS is usually used in peer-reviewed scientific journals instead of mho.

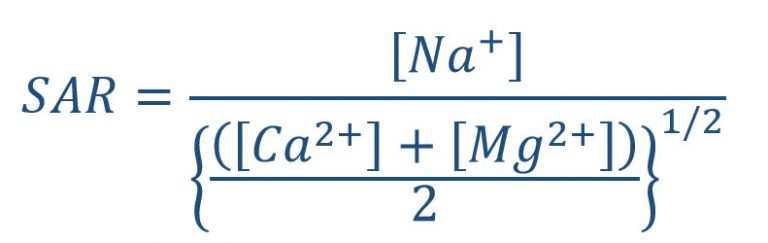

Sodium Adsorption Ratio and Sodicity

Soil sodicity is caused by excessive saturation of Na+ ions at the soil cation exchange sites (negative charges of clay and humus particles that attract positively charged chemical ions). Sodicity directly affects soils as high Na+ levels compared to calcium (Ca2+) in combination with low salt levels can promote “soil dispersion”, which is the opposite of flocculation. Soil dispersion causes the breakdown of soil aggregates, resulting in poor soil structure (low “tilth” qualities). Due to the poor soil structure, sodic soils have dense soil layers, resulting in very slow permeability of water, air, and other contaminants through the soil profile. It is important to note that if Na+ is present as a salt, it will not cause dispersion as the positive charges of Na+ ions will be neutralized by the negatively charged chemical ions such as sulfates (SO42-) or chloride (Cl–). However, due to the constant exchange of positively charged ions, such as Ca2+, magnesium (Mg2+), and Na+, between soil water and the soil’s clay and humus particles, high levels of Na+ in the soil water can result in sodicity, as more negative charges can become saturated with Na+.

When sodic soils occur near the soil surface, they can sometimes appear slightly darker than the surrounding soils. This occurs because the forces that typically hold the clay and organic matter are disrupted, and instead, the organic matter is forced out of the soil aggregates. Ponded water on a flat surface can also be an indicator. However, the only way to truly determine if a soil is sodic is by sampling the affected areas and getting them analyzed by a soil testing laboratory. Historically, the Exchangeable Sodium Percentage (ESP) test has been used to analyze soils for sodicity. However, over time, ESP has been replaced by the Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR) in most regional soil laboratories. As a result, SAR values can be substituted for ESP (Oster et al., 1999).

Soil SAR is a measure of the ratio of sodium (Na+) relative to calcium (Ca2+) and magnesium (Mg2+) in the water extract (solution phase) from a saturated soil paste (Eq. 1). The units of Ca2+, Mg2+, and Na+ are milliequivalent/liter [meq/L) or mmol(c)/L].

For classification purposes, a soil is considered sodic if its SAR levels are 13 or more; however, these values are general guidelines and don’t imply that lower numbers will not result in detrimental effects related to soil sodicity, especially for shrinking and expanding clays. Based on the findings of NDSU research for shrinking and swelling types of clays, if soil results for SAR are more than 5 and the Electrical Conductivity (EC) is less than two millimhos per centimeter (mmhos/cm), movement of soil water may be restricted due to swelling, dispersion, or both.

Cation Exchange Capacity

Soil Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) refers to the negative charges of a particular soil to adsorb and exchange positively charged chemical ions such as Calcium (Ca2+), Magnesium (Mg2+), Sodium (Na+), Hydrogen (H+), and Potassium (K+). These negative charges are provided by clay and humus (the most decomposed form of organic matter) particles, so as soil clay and organic matter contents increase, CEC will also increase. CEC ranges from 1 to 100, with sandy soils having the lowest values, whereas clays will have the highest values. Soils with a large amount of kaolinite will have lower CEC values, and soils with more smectite will have higher values. Kaolinite is more common in soils of the southeastern United States, while soils in the Great Plains have more smectite. The most common mineralogy is “mixed”, so many soils will have intermediate CEC values. CEC measurement units are milliequivalents/100 grams of soil (meq/100 g) or cmol (+)/kg (S.I. unit). Each meq/100 grams of soil is equal to each cmol (+)/kg.

Since soil CEC measurements vary with varying soil pH (CEC is lowest at pH levels of 3.5 to 4.0 and increases with an increase in pH), it is commonly measured at a pH of 7.0. There are two methods to measure soil CEC: by using the “Summation or Addition method” or by measuring it through the “Sodium (Na+) Saturation and Ammonium (NH+4) Extraction method”. The summation or addition method adds the concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, H+, and K+ from a soil extract, generally resulting in artificially higher CEC values, especially when the levels of water-soluble salts are in excess, as reflected by a higher electrical conductivity (EC). The Na+ saturation and NH+4 extraction method is considered more accurate, and the CEC value measured by using this method is regarded as the “True Soil CEC”. In this method, first, the soil’s negative charges are saturated with NH+4 ions, and then NH+4 is replaced by Na+. CEC is then determined by calculating the amount of NH+4 that was replaced by Na+. CEC is a very important chemical property that reflects soil functions, such as the ability of a soil to retain and exchange essential plant nutrients, and helps calculate rates of soil amendments to remediate sodicity.

Soil base saturation or percent base saturation is the measurement of the proportion of soil CEC (negatively charged exchange sites) that is occupied (adsorbed) by the basic cations such as Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and K+. The unit for measuring base saturation is percent. An alkaline soil pH of 7.0 or more is indicative of a high base saturation. In contrast, a highly acidic soil pH is indicative of a higher percentage of soil CEC occupied by acidic cations like H+ and Aluminum (Al3+).

Regional State Nutrient Recommendations

This curated collection of state-specific nutrient recommendations guides the management of field, vegetable, and fruit crops across the Midwest. Resources span Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Kansas, South Dakota, North Dakota, Iowa, Missouri, Illinois, Wisconsin, and the Tri-State region, with emphasis on soil test interpretation, fertilizer rates, and limestone needs. Developed by leading land-grant universities, these publications support informed nutrient planning tailored to local conditions and cropping systems.