Soil Physical Properties

Soil physical properties include both inherent and dynamic soil properties. Inherent properties include soil texture, soil parent materials, and soil depth. Dynamic properties are those that can be influenced by management, including infiltration, aggregate stability, available soil water-holding capacity, soil organic matter, soil porosity, compaction layers, crusting, bulk density, and soil structure. Optimal soil physical properties reduce limitations to root growth and productivity, improve seedling emergence, nutrient and water retention, infiltration, and movement of air and water within the soil profile. Physical properties are directly related to optimal chemical and biological properties, which, together, improve nutrient and water cycling, as well as other key soil functions.

Permeability and Infiltration

Permeability is the ability of soils to transmit water and air through its layers. Soil permeability is significantly influenced by porosity, the type and size of pores, and properties that impact porosity, including organic matter levels, aggregation, the shrinking and swelling of clay particles, dispersion caused by low calcium levels versus sodium and magnesium, and traffic.

Infiltration is the rate at which water moves through soil layers and is measured as saturated hydraulic conductivity. It plays a critical role in crop health and environmental resilience. For example, increasing a soil’s water-holding capacity by just half an inch can allow a corn field to go two extra days without rain during pollination. Across the Mississippi River basin, such gains in infiltration equate to the volume of water flowing over Niagara Falls for nearly 12 weeks. Infiltration is influenced by soil texture, structure (especially aggregation), initial moisture levels, pore size and type, and the balance of calcium versus sodium and magnesium. Well-structured soils with diverse pore sizes support faster infiltration and better water retention.

Structure

Soil structure (aggregates) is impacted by inherent soil properties (particle composition, salts) and management, impacting dynamic soil properties (including aggregate stability, organic matter levels, calcium levels versus sodium and magnesium, air to water ratio, and temperature).

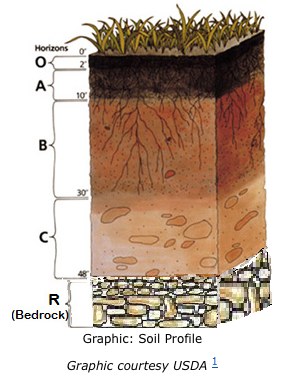

Soil Profile

The soil profile refers to the arrangement of soil layers extending downward from the soil surface. These individual layers are called soil horizons and differ in several easily observed soil properties, such as color, texture, structure, and thickness. Other properties, such as chemical and mineral content, consistency, and reaction, require special testing.

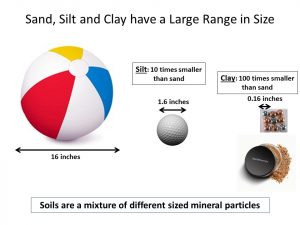

Texture

Soil texture refers to the particle size distribution and relative proportion of sand, silt, and clay in the mineral component of soils. The percentage of sand, silt, and clay can affect available water capacity, compaction, structure, bulk density, and porosity, as well as other non-physical soil properties.

Aggregation and Aggregate Stability

Soil aggregation refers to the clumping of mineral and organic particles into aggregates, held together by organic matter and fungal threads. This process is influenced by soil texture, composition, and biological activity. Aggregates help prevent runoff, support infiltration, and contribute to soil structure. Granular aggregates, common in surface horizons enriched with organic matter, promote water capture and root growth. Soil structures vary—single-grain, blocky, platy, prismatic, and massive—each affecting pore space and water movement differently.

Aggregate stability is the soil’s ability to resist breakdown when exposed to disruptive forces like raindrops, water, wind erosion, swelling, or tillage. It directly affects infiltration, root growth, erosion resistance, water capacity, nutrient availability, and microbial activity. Stability varies with soil type and can be evaluated using the slake test. Stable aggregates with diverse pore sizes are essential for maintaining soil structure and supporting key soil processes and productivity.

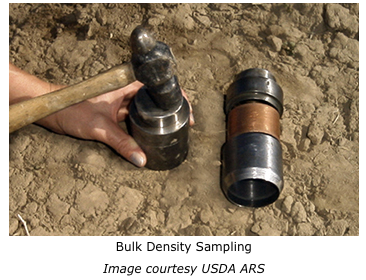

Bulk Density

Bulk density is the mass of mineral and organic soil particles divided by the total volume they occupy. It serves as a key indicator of soil compaction and overall soil health, influencing how rapidly water infiltrates the soil and helping identify areas of concern. Bulk density affects rooting depth, available water capacity, soil porosity, nutrient availability, and microbial activity—all of which shape essential soil processes and productivity.

Bulk density varies by soil type. For example, clay particles are much smaller than sand particles and have a greater surface area, resulting in more pore spaces. As a result, dry clay soils typically have lower bulk density values than sandy soils. Factors such as organic matter content, soil texture, and structure also influence bulk density, making it a valuable metric for assessing soil function and resilience.

Compaction

Soil compaction occurs when soil particles are compressed together, resulting in reduced pore space between them, which can impede root growth. Soil compaction can be caused by low organic matter levels, poor structure, heavier texture, dispersion resulting from low calcium levels compared to sodium and magnesium, tillage, and traffic.

Temperature

Soil temperature refers to the temperature measured at a specific depth within the soil. Soil temperature is a factor that influences the physical, chemical, and microbiological processes that take place in soil. Many biological processes, including seed germination, plant emergence, microbial activity, nutrient cycling, and soil respiration, are functions of soil temperature. Cropping practices, including the use of cover crops, crop rotations, grazing of crop residues or cover crops, removal of crop residues, and tillage, affect soil temperature.

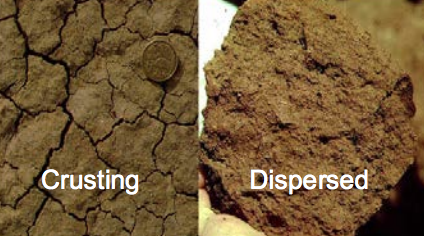

Crusting

Soil crusting is the formation of a hard, compact layer at the soil surface, characterized by reduced porosity and high penetration resistance. This crusting is associated with reduced water infiltration, restricted seedling emergence, and increased erosion.

Available Water Capacity

Soil Water Holding Capacity is the ability of a soil to hold the maximum amount of water between the field capacity and permanent wilting point moisture levels. It is affected by soil texture, organic matter level, porosity, and pore sizes.

Available water capacity refers to the amount of water that a soil can store and make available for plant use. In general, it is the water held between the field capacity and the wilting point.

Plant Available Water is the part of water held between the field capacity and the permanent wilting point moisture levels. The actual amount of water absorbed by the plants depends upon plant water-use, growth stage, and rooting structure and depths.

Moisture

Soil moisture refers to the total amount of water held in soil pores at any given point, encompassing gravitational, capillary, and hygroscopic types of water. Soil moisture is affected by porosity, permeability, compaction, and bulk density.

Porosity

Soil porosity refers to the volume of pore spaces between mineral and organic particles, which are occupied by air and water. These pores—classified as macro, capillary, and micro—are essential for the movement of water, air, and nutrients, as well as for creating habitats for soil organisms like fungi, nematodes, insects, and arachnids. Pore space also facilitates seed germination and provides pathways for root growth and penetration. The distribution of pore sizes influences water-holding capacity, plant-available water, infiltration rate, and the air-to-water ratio. Porosity is shaped by factors such as organic matter content, aggregation, clay swelling and shrinking, calcium-to-sodium ratios, tillage, and soil compaction from traffic.